Imagine peering into two seemingly distinct mirrors, each reflecting a familiar story, a resonant idea, or a critical dataset. At first glance, you might spot obvious differences: one might be gilded, the other plain; one vibrant, the other muted. But as you look closer, guided by a discerning eye, you begin to uncover hidden patterns, surprising echoes, and significant divergences. This isn't just a casual observation; it's the heart of Comparative Analysis: Different Adaptations and Reinterpretations. It's how we move beyond simply seeing to truly understanding how individual entities relate, influence, and diverge from one another, pushing the boundaries of our knowledge and sparking profound insights.

Whether you're dissecting classic literature, unraveling complex social phenomena, or evaluating competing theories, comparative analysis is your most potent tool for making sense of a multifaceted world. It's less about finding a single "correct" answer and more about enriching your perspective, sharpening your critical faculties, and building arguments that stand on a foundation of robust, multi-sourced understanding.

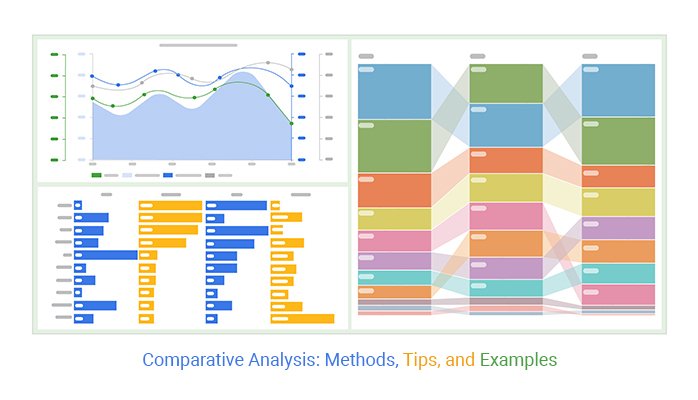

At a Glance: Your Toolkit for Deeper Understanding

- Move Beyond the Single Source: Avoid the "n of 1" problem by comparing multiple texts or entities, leading to richer, less simplistic conclusions.

- Three Core Approaches: Master Coordinate (A ↔ B), Subordinate (A → B), and Hybrid comparisons for versatile analytical power.

- Structure Your Argument: Choose between "AAA/BBB" or "ABABAB" patterns to organize your comparative points effectively.

- Significance is Key: Don't just list similarities and differences; always ask why they matter and what new understanding they reveal.

- Treat Thesis as Hypothesis: Be open to your argument evolving as you gather and interpret evidence.

- Practical Application: Ideal for everything from literary adaptations and genre studies to social science case studies and theory testing.

- Avoid Pitfalls: Guard against vague theses, imbalanced analysis, and structural confusion with proactive planning.

Why Comparison Isn't Just an Option – It's Essential

In an increasingly interconnected world, where information bombards us from every angle, the ability to compare and contrast isn't just a useful skill; it's a fundamental necessity. Comparative analysis is the intellectual superpower that allows you to make an argument about the relationship between two or more texts, datasets, or entities by zeroing in on their prominent similarities and differences.

Think of it this way: If you only ever read one version of a fairytale, you'd believe that version is the story. But compare it to another culture's adaptation, or even a modern retelling, and suddenly you see the core themes differently. You notice how cultural values shape narratives, how reinterpretations reflect contemporary anxieties, and how enduring ideas transcend specific forms.

This analytical process isn't confined to the humanities. In the social sciences, comparison lies at the very heart of most research. Whether you're analyzing interview transcripts, examining different policies, or studying varied communities, you're constantly looking for patterns, divergences, and causal links that emerge from comparative inquiry.

The "N of 1" Problem and How Comparison Solves It:

One of the biggest traps in analysis is relying on a single source or case study – the dreaded "n of 1" problem. If your conclusions are based solely on one example, they risk being overly specific, ungeneralizable, or even skewed by unique circumstances. Comparative analysis smashes this problem by demanding a broader perspective. By putting multiple sources in conversation, you gain:

- Richer Understanding: You see nuances and complexities that a single lens would miss.

- Robust Conclusions: Your arguments become less prone to oversimplification and stand on firmer intellectual ground.

- A Bridge to Deeper Research: It's often the natural stepping stone from basic single-source analysis to more sophisticated research essays and doctoral studies.

The Three Pillars of Comparative Analysis: Your Analytical Playbook

Not all comparisons are created equal. Depending on your objective, you'll employ different strategic approaches. Understanding these three fundamental types will give you the flexibility to tackle any comparative challenge.

1. Coordinate Analysis (A ↔ B): Finding Common Ground and Striking Differences

This is perhaps the most intuitive form of comparison. You're bringing two (or more) texts or entities together based on a shared element, then exploring their relationship. The goal is to argue about how they are alike and different, and crucially, what the significance of those similarities and differences is.

- The Blueprint: A ↔ B (Entity A compared with Entity B).

- When to Use It:

- Comparing two novels by the same author to trace thematic evolution.

- Analyzing two film adaptations of the same book to understand directorial choices.

- Evaluating two datasets from similar experiments to identify consistent patterns or anomalies.

- Comparing two national policies designed to address the same social issue.

- Example: You might compare two different film adaptations of Shakespeare's Hamlet. You'd look at how Laurence Olivier's 1948 version and Kenneth Branagh's 1996 version interpret Hamlet's madness, the role of Ophelia, or the aesthetic choices made for Elsinore. The shared element is Hamlet; the comparison reveals how different creative teams reinterpreted the core text.

2. Subordinate Analysis (A → B or B → A): The Lens and the Test

Subordinate analysis introduces a hierarchy. One text or entity serves as a "lens" through which to understand another, or it acts as a "case study" to test the validity or limits of a theory.

- The Blueprint: A → B (A explains B) or B → A (B tests A).

- When to Use It:

- Using a theoretical text (A) to illuminate and explain a specific work of art or social phenomenon (B). For instance, applying feminist theory to analyze the portrayal of female characters in a contemporary novel.

- Using a case study or work of art (B) to "test" the usefulness or limitations of a specific theory (A). For example, examining a local community's response to climate change to evaluate the applicability of a broader sociological theory of social movements.

- Example: Imagine you're exploring the concept of "the uncanny" as theorized by Sigmund Freud (A). You could then apply Freud's framework to analyze the pervasive unsettling atmosphere in a specific horror film like Get Out (B). The film isn't just scary; through Freud's lens, you understand why and how it creates that particular psychological effect. Alternatively, you might analyze Get Out (B) to see if Freud's theory (A) fully accounts for its unique blend of horror and social commentary, perhaps finding its limits.

3. Hybrid Analysis [A → (B ↔ C) or (B ↔ C) → A]: The Scholarly Synthesis

As the name suggests, hybrid analysis combines elements of both coordinate and subordinate approaches. This is often the realm of more complex, sophisticated, and scholarly comparisons, allowing for multi-layered insights.

- The Blueprint: [A → (B ↔ C)] (Theory A illuminates a comparison between B and C) or [(B ↔ C) → A] (A comparison between B and C helps refine or challenge Theory A).

- When to Use It:

- Applying a specific critical theory (A) to compare two adaptations of the same source material (B and C).

- Using the comparison between two different cultural phenomena (B and C) to refine or illustrate a broader theoretical concept (A).

- Example: You might use postcolonial theory (A) as a framework to compare two different historical retellings of colonialism (B and C) – perhaps a traditional Western account versus a contemporary indigenous perspective. The theory not only helps you identify similarities and differences in narrative strategies but also reveals the underlying power structures at play in each retelling.

Mastering the Art: How to Conduct a Comparative Analysis That Resonates

Moving from recognizing the types of comparison to actually doing it well requires a structured approach. Think of it as a creative journey, where you're constantly refining your map as you explore new terrain.

1. Frame Your Inquiry: Setting the Stage for Discovery

Before you dive in, you need a clear sense of purpose. Effective framing involves:

- Identifying the Core Question: What are you trying to understand by bringing these texts/entities together?

- Defining Your Entities: Clearly identify what each text or entity does independently. What are its unique characteristics, arguments, or artistic merits?

- Noting Connections: Brainstorm immediate, surface-level connections or contrasts. Where do they overlap? Where do they diverge?

- Imagining Significance: Even at this early stage, start to ponder: How do these connections (or their absence) complicate, confirm, or alter our existing understandings of the subject matter, the authors, or the broader context? This early rumination on "why it matters" is crucial.

2. Gather Your Evidence: Building Your Inventory of Insights

This is where you move beyond general impressions and start collecting concrete data. It’s about creating an inventory of "touch points" between your texts.

- Systematic Inventory: Create a chart, list, or digital document to systematically log shared or unshared elements. This could include:

- Themes and Motifs: Recurring ideas, symbols, or imagery.

- Arguments and Claims: The main points each text makes.

- Methodologies: How data is collected, analyzed, or presented.

- Characters/Actors: Their roles, development, and interactions.

- Settings/Contexts: Where and when things happen.

- Stylistic Choices: Narrative techniques, artistic styles, language use.

- Specific Examples: Concrete instances that illustrate a point.

- Detailed Notes: Don't just list; add brief explanations or quotes for each item. This stage is less about making an argument and more about meticulous observation and documentation.

3. Articulate Significance: Answering the "So What?"

This is the intellectual cornerstone of any good comparative analysis. It's not enough to simply say "X is similar to Y" or "A is different from B." You must explain why those similarities or differences are important.

- The "Why It Matters" Question: Consistently ask yourself: What new understanding emerges from this comparison? How does it challenge, confirm, or refine a previous idea? What implications does it have for interpretation, theory, or practice?

- Beyond Surface-Level: Push past obvious comparisons to uncover deeper, often less apparent, insights. For example, two film adaptations might both depict a tragic ending (similarity), but the way they achieve that tragedy, or the message it conveys, could be profoundly different and reveal much about the directors' worldviews.

4. Structure Your Argument: Guiding Your Reader Through the Comparison

Comparative essays can be tricky to organize because you're constantly juggling multiple entities. Two common structural patterns help maintain clarity:

- The Block Method (AAA/BBB): All About A, Then All About B

- How it Works: You discuss all your points about text/entity A in detail, then transition to discussing all corresponding points about text/entity B.

- Best For: When comparisons are relatively straightforward, or when one entity serves as a clear baseline. It works well if the points of comparison are largely identical across texts.

- Caution: Requires very strong transitions to explicitly link back to A's points when discussing B. Avoid simply summarizing B after A; you must actively compare.

- The Point-by-Point Method (ABABAB): Alternating Perspectives

- How it Works: You discuss a specific point of comparison, contrasting A and B within that single paragraph or section, then move to the next point of comparison, again contrasting A and B.

- Best For: More complex arguments where ideas build progressively, or when the relationship between A and B needs to be constantly foregrounded. It naturally facilitates deeper comparison by keeping both entities in immediate conversation.

- Caution: Ensure you dedicate enough space to each entity within a point to avoid a "ping-pong" effect where ideas feel rushed.

Your choice of structure depends entirely on the goal of your argument. If you're demonstrating how two works handle a theme very differently, ABABAB might be stronger. If you're showing how a particular theory applies across two distinct cases, AAA/BBB could be effective if each case needs thorough individual explanation.

Actionable Tips for Sharper Insights

Even with a solid framework, a few critical habits can elevate your comparative analysis from good to exceptional.

- Treat Your Thesis as a Hypothesis: Don't view your initial thesis statement as an immutable law. Instead, consider it a working hypothesis you'll test, refine, and potentially even alter as you delve deeper into your evidence. This flexible approach allows for genuine discovery.

- Create That Inventory Early: Before you even try to draft a thesis, meticulously inventory the touch points between your texts. This isn't wasted time; it's the foundation upon which strong, evidence-based arguments are built. The thesis should emerge from this comparative data, not be imposed upon it.

- Justify, Justify, Justify: Make it a habit to constantly ask yourself (and, if you're teaching, your students) to justify the significance of every claim. If you find yourself merely stating a similarity or difference, stop and ask: "So what? Why does this matter? What does it reveal?"

Navigating the Treacherous Waters: Common Pitfalls and How to Avoid Them

Comparative analysis, while powerful, comes with its own set of potential traps. Being aware of these common missteps will help you steer clear of them.

The "Just Listing" Trap in Coordinate Analysis

- The Pitfall: A thesis that merely states "Text A and Text B have similarities and differences" without explaining the significance of those relationships. Your essay then becomes a disconnected list of observations rather than a coherent argument.

- The Solution: This circles back to the importance of the inventory stage. Before formulating your thesis, immerse yourself in the comparative data. Let your argument about why these similarities and differences matter emerge from your findings. Your thesis should articulate a clear argument about the implications of the comparison, not just its existence. For example, instead of "The Little Mermaid movie and book have similarities and differences," aim for something like, "While both versions of The Little Mermaid explore themes of sacrifice and transformation, the film's shift in focus from divine reward to romantic love reflects changing societal values regarding female autonomy."

The Imbalance Bog in Subordinate Analysis

- The Pitfall: Giving disproportionate weight to one source over another. In an A → B analysis, you might spend too much time summarizing the theory (A) and not enough applying it meaningfully to the case study (B), or vice-versa. This leads to biased or incomplete analysis.

- The Solution: Emphasize engaging with counterevidence and counterarguments. If you're using a theory as a lens, don't just find examples that fit; actively look for instances where the theory might struggle to explain phenomena, or where a different interpretation is possible. Remember that the "lens" approach and the "test a theory" approach are two sides of the same coin in real-world application; a good analysis will often do both, balancing the exploration of usefulness with an acknowledgment of limitations.

Structural Conundrums in Any Comparative Analysis

- The Pitfall: Getting lost in the back-and-forth between texts, resulting in confusing transitions or paragraphs that lack a clear comparative focus. The reader struggles to follow your train of thought.

- The Solution: This is where selecting the right structure (AAA/BBB or ABABAB) before drafting becomes critical. Once you've chosen, commit to it and use explicit transition words and phrases to guide your reader. Use topic sentences that clearly state the point of comparison and indicate which entities are being discussed. For example, "While Author X uses vivid imagery to evoke setting, Author Y relies more heavily on dialogue to achieve a similar effect," clearly sets up a comparison.

Beyond the Classroom: Comparative Analysis in the Real World of Research

The principles of comparative analysis aren't confined to academic essays. They are fundamental to how knowledge is generated in countless fields, particularly within the social sciences.

- Constant Comparative Analysis: A cornerstone of grounded theory, this iterative process involves comparing one data entity (an interview, an observation, a document) with others to identify emerging patterns, categories, and conceptual models of relationships. It's a continuous cycle of data collection, coding, and comparison, allowing theories to emerge from the data itself.

- Case Study Research: Here, comparative analysis is a primary task. Researchers often compile multiple cases with an anticipated comparison in mind, sometimes even against hypothetical reference groups. This approach helps identify commonalities, unique factors, and causal pathways. For instance, comparing the public health responses of different nations to a global pandemic provides invaluable insights into effective strategies and systemic failures.

- Qualitative Comparative Approaches: While some traditions, like Clifford Geertz's "thick description," prioritize intensive, context-rich descriptions of a single case over explicit comparison, many qualitative methods actively engage in intensive examination of a few cases to draw nuanced comparative conclusions. The strength of this approach lies in its ability to delve deeply into contextual factors that might be overlooked in large-N studies.

The Power of Adaptation: Applying Your Comparative Lens to Creative Reinterpretations

The "Different Adaptations and Reinterpretations" part of our keyword truly shines when you apply these comparative analytical frameworks to creative works. Every adaptation, every remake, every new translation is inherently a comparative act – a reinterpretation of a source through a new lens, for a new audience, or in a new medium.

- Analyzing Literary Adaptations: How does a novel translate to the big screen? You can use coordinate analysis to compare character arcs, narrative pacing, and thematic emphasis. What was gained, what was lost, and what was radically transformed? A subordinate analysis might use narrative theory to explain why certain changes were made by the director.

- Exploring Cultural Reinterpretations: Folk tales, myths, and historical events are constantly reinterpreted across cultures and generations. Comparing different versions of Cinderella from various countries reveals how societal values regarding beauty, class, and destiny are embedded in the narrative. A hybrid analysis could use psychological theories to compare how different cultures interpret the "hero's journey" archetype in their myths.

- Gaming and Media Spin-offs: How does a beloved book series translate into a video game? Or a comic book into a TV show? This is rich territory for comparative analysis, examining how interactive elements, visual storytelling, or episodic structures reinterpret the original narrative, characters, and world-building.

- Political and Social Reinterpretations: Even political speeches or historical events can be "reinterpreted" by different media outlets or political factions. Comparative analysis allows you to dissect these reinterpretations, identifying biases, rhetorical strategies, and the underlying agendas shaping the narrative.

By actively applying the frameworks of coordinate, subordinate, and hybrid analysis, you unlock a deeper understanding of not just the individual works, but also the creative, cultural, and political forces that drive adaptation and reinterpretation.

Stepping Up Your Analytical Game: What Comes Next?

Comparative analysis isn't just a standalone skill; it's a foundational one that scaffolds into more advanced academic and professional endeavors.

- Increased Complexity: Once you've mastered comparing two entities, you can easily scale up to comparing more sources, or changing the axes of your comparison (e.g., instead of just comparing themes, also compare narrative structure).

- Gateway to Research: Many research essays, particularly in the social sciences and humanities, are extensions of hybrid comparative analysis. You'll move from comparing specific cases to using those comparisons to build and support a broader theoretical argument.

- Theoretical Exploration: Comparative assignments are excellent vehicles for exploring and understanding different theoretical approaches. By applying various theories as lenses, you can see their strengths and weaknesses in practice, preparing you for capstone research or advanced doctoral work.

- Real-World Problem Solving: In professional settings, whether you're evaluating competing business strategies, analyzing policy alternatives, or comparing different technological solutions, the ability to conduct rigorous comparative analysis is indispensable. It empowers you to make informed decisions based on comprehensive understanding rather than superficial assessment.

Ultimately, embracing comparative analysis means embracing a mindset of nuanced inquiry. It’s about cultivating the intellectual muscle to see not just the individual parts, but also the intricate web of relationships that connect them. It’s about moving beyond simply recognizing differences and similarities to truly understanding their significance, their implications, and the richer, more complex narratives they help us to write.